- Home

- Gerty Dambury

The Restless Page 15

The Restless Read online

Page 15

“In no time at all, in all the towns around, men and women, from the oldest to the youngest, had saddled their horses, prodded their donkeys, grabbed their swords, sharpened their knives, broken off enormous branches from mango trees, and resuscitated those oldtime whips that had been hidden under what passed for goodwill. But in the wink of an eye, the homicidal gendarme and his wife had been smuggled out and sent away to, I hope, the coldest part of their country. Over there, in the Jura Mountains, where they exiled our great ancestor, Toussaint Louverture—exiled to death. Let every single part of their bodies freeze! Let them starve to death!

“The organized escape only succeeded in making people even angrier. Instead of giving the crowd the ones responsible for the outburst of violence, as scapegoats for what had happened, they chose to evoke The Law—that symbol of power, that ensemble of rules exasperating everybody till the end of time. So lightning struck all the government buildings. The court burned. The prefecture burned. The prison burned. Police headquarters burned. The schools and the factories burned, the cane fields burned. And all the shops of the sellouts and collaborators burned. And the whole town of Basse-Terre and the village of Gourbeyre would have burned, too, if they didn’t finally find a negotiator that people believed in and listened to—when the fury started to abate, when people could start seeing each other again, when that thing that can’t be named came back into focus. When they began to come to grips with the extent of the damage caused by losing control.”

While this story was finishing, I quietly exited La Pointe, accompanied by the last words of my mother’s witnessing, words falling gently one after the other into my ears, words attending me even despite the vertigo threatening to overtake me, widening the space between my body and myself.

I left my dirty clothes, my bloody body, my confusion in rue Frébault and said goodbye to my unborn child, who will only ever know me through photographic portraits, those artificial poses struck in local studios.

15.

God of Thunder! What in heaven’s name are my poor old ears hearing?

It would’ve been better if I hadn’t come back, dragging my bones around just to witness another earthquake in this country I call mine! Lord help us!

But, I ask you, tonnèdidyé, what am I supposed to do with only one leg? Useless to boot! Godammit all to hell!

If the good Lord can’t even find it in Him to grant us a little peace, a full stomach, a roof over our heads—the least a person can ask for himself and his descendants—why am I even holding out for a shitty quadrille ball in a phony paradise with angels who don’t give a damn. They’ve seen too much crap year after year! And His Majesty himself won’t even raise a finger!

Yeah, it’s starting again. Not that it’s ever really over.

I try not to think about it, but it’s coming back like yesterday.

I tried to bury it when they buried me. All those long sad nights when we watched over the dead, when I went to see families silent as horror itself, real horror, the one that cuts your vocal cords in one quick slice, like a razor.

I can see those long lines around the bodies, people stopping in front of eyes now shut, trying to take it all in. It’s the last time, really, the last time they’re going to see this boy, going to see how even in death anger lingers in a creased forehead, a pinched mouth—proving that death brings not a bit of the peace we’re promised. And underneath the clothes, the last clothes he wore, there’s blood, dried blood, wiped clean by the careful hands of the man at the funeral parlor, as smooth as the Tordoncan kid who straightened out my arm that got stuck when I died.

A glance, the sign of the cross, a parade of the defeated—and here’s just one more . . . I see those get-togethers where they hold back tears, let nothing show: not pain, anger—nothing. It’s like they’ve accepted it, yet they’re still thinking about how to get even, whack the killers—one day, somehow, one way or the other.

They’ve been taking detours, skirting trouble, for such a long time, but one day it boils over. They’ll explode and then go back to life as usual.

Because patience and time accomplish more than force or rage.

Everything in its time. Tout’ cochon ni sanmdi a yo!

Nobody escapes fate. Sa ki la pou’w dlo pa’a chayé’y!

Pass around the proverbs at the communal table! Pass them around; share them. Those ready-made words that help us wait.

Yeah, I see them, those long wakes accompanied by the sounds of the conch in the night, from one hill to the other—our call to prayer—and those slow and dignified burials, the long march of dark colors followed by the scent of clothes just pulled out of storage.

How is it possible we let the little one see what she saw? Who could’ve imagined the simple dismissal of a teacher would’ve led to that child bearing witness to such butchery? What do we think will come of all this, this upset born of what seemed like a minor incident in a child’s life, an event in the daily routine of some thirty little girls, a tiny incident about nothing at all—at first—but one that spread from room to room, class to class, in a school where rebellion was just around the corner.

A miniscule spark that ends up igniting a powder keg and causing an inferno. We’ve lit that fire so many times in the streets, in the squares, at the shore, on the roads: barricaded bridges, overturned and burned cars. Shots fired, men arrested and jailed, the dead quietly buried, their bodies disfigured by blows, old men beaten and abandoned in the street like dogs thrown in the garbage in the middle of the night.

A long list of names will only get longer with all those voices crying out, in a country where peace will never come, where it’s too dark, where fury smolders on and on. A whole host of voices is emerging from a chasm Émilienne didn’t even know existed, but that she’s now starting to detect. Now that she’s decided she needs to know, to learn, to hear, to ask why such violence reigns, why a woman she and her classmates love so much could be targeted.

So the two fires have come together: the flame of the teacher’s disappearance has added to the great blaze of injustice. And what a foolish mistake to have lit that spark—which seemed so harmless—because it will never go out now. And it’s made the dead rise up and mix their voices with the living.

What idiot doesn’t understand that dry branches always feed a fire? We’re a forest of dry branches just waiting for a spark. How can they not understand that, given how long this has been going on?

That forest! That’s what her father ought to speak to her about! Why the hell doesn’t the bastard come home?

Given everything that’s happened in town today, I can’t believe that man isn’t worrying about what’s become of his family, if somebody might be dead or wounded, if the two and a half floors of the unfinished house he cares about so much are still standing.

16.

The chorus? The callers?

What should we name ourselves now? We don’t really know anymore!

We’re overwhelmed, and it’s coming from all sides.

The voices aren’t paying attention to us. The instruments are playing all at once.

The dancing’s chaotic.

But we have to hold on for the last figure,

The finale, the last gasp.

Ladies and gentlemen, make way for pastourelle!

THE FOURTH FIGURE: PASTOURELLE

1.

Friday, May 26, 1967. Our family’s scattered all over town.

We don’t know where our brothers and sisters are. They should’ve been home from school by now.

Émile’s managed to return from Carnot. His teachers let them leave right away, but there’s no news from Emmett or from Émilio, and not a word from Émelie.

Mama’s having trouble breathing. She’s holding her stomach, like Émelie does when she’s upset.

Emmy pulls me into the bathroom and washes me from head to toe. I want to tell her that I know how to wash myself, but I understand she wants to make sure I’m all there.

I fe

el kind of weak inside, but at the same time I know my heart is hard, hard like the faces of the fishermen I saw in their boats on the Darse—while they were watching the gendarmes on the docks chase those young guys throwing bottles and stones.

I’m afraid for Émelie, Emmett, and Emilio.

I’m afraid for you, Papa, but I don’t know what to think about you either. I wonder if you were really there at that meeting, in the middle of that violence.

So I let Emmy wash me. I try to start breathing again without being angry, but I can’t.

I don’t feel like crying or tearing my dress or scratching my face. It’s not me I feel like hitting and scratching.

2.

Standing a few meters from Absalon’s house, I was thinking about everything that’d happened that afternoon, how I had one of his shirts on, and I’d shepherded his little girl all across the city and through the rioting.

I was thinking he sure wouldn’t have risked his life for me or one of mine. We were on different sides of the fence, like opponents—but maybe I just couldn’t manage to see all his family as enemies, adversaries you had to beat no matter what the cost. I thought about the warm little body of his daughter in my arms. That child had never shunned me; she’d played with my tools, followed us around while we worked. She was a strange little kid who didn’t talk like other children, who asked all kinds of questions. But I’d never seen in how she looked at me, in how she acted towards me, anything that said she didn’t respect me, anything that said she might not even have some affection for me.

I was glad I’d brought her home.

But I wondered what would happen next. Things weren’t going to stop just like that.

The gendarmes were probably going after people, arresting them, and putting some in prison, starting with the union guys. I was sure Julien would be one of the major suspects, and even if I trusted him, I was hoping he’d keep his mouth shut. I hoped nobody knew me well enough to find me, however they might try.

I was wondering if when everything calmed down, we’d be able to pick life back up the way it’d been before and whether what had happened would change something between us and the bosses, with the people who really ran things—the ones we hardly ever get a glimpse of, except when we’re supposed to fix up their houses when they start to get shabby, or when they need to know how to put up a wall, or when they want to buy cheaper material.

I couldn’t see a single bus on the horizon. I’d heard the buses had gone back to their terminal, in the outskirts, in order to keep from being set on fire, from being caught in the same frenzy of wrecked and burned cars that had erupted in Basse-Terre last March.

Thinking about Basse-Terre, the authorities must have known that the rioting would happen again; they must have decided this time they’d be prepared for it. And, yeah, they were ready all right—ready to shoot anything that got in their way.

I was going to have to walk home, to avoid the major roads. I was thinking that when the boss’s Dauphine stopped in front of me: “Guy-Albè, monté."

He opened the car door for me. He was serious, very quiet. I’d never seen him like that.

“Ola ou kay? Ou ka rantré?”

“Fo an monté a kaz, patron.”

“An ké menné’w, pa ni vwati ankè.”

That was it, all we said till we got to my place. It was the time I like best, the time of day when the sun has just started to set, one of those moments that makes you calm, like in the early morning, when you can look around without the sun washing everything out. I like this special time when night starts to creep in. I like it too because the animals all seem to have something to say: the birds share their adventures with those coming back to nest and with those getting ready to retire elsewhere for the evening, one last salvo of chirping and cooing—while the cows stretch their necks up to the sky and open their mouths to bid the day farewell. The birds whiz around in all directions, predict rain, change their minds, fly away somewhere else—heading out to the sea you can’t detect from here, but you can feel it in the air, in the beautiful light that’s ours. So what if it’s the only country I know, and only some of it at that—some of Grande-Terre. I love the color of the land, the light, the people.

Sitting at my side, the boss seemed to enjoy the silence. I was wondering where the hell he could’ve been during the events, if he’d seen the bodies on the ground, the blood in the streets, the anger of the young guys and the men like me. I wondered, too, if he knew I’d brought his daughter home.

It seemed like he was listening to my thoughts because he started to speak, and the man who spoke wasn’t the man I knew. The new man’s voice caught in his throat; his words came out softly, without the aggression I’d always heard there, and those words said that what had just occurred was a horror. That voice, I understood, had seen dead men on La Place, wounded people in town, men stopped in their tracks while they were running, a father cut down while he was holding his child’s hand. That voice had seen bodies hurriedly carted off, men wiped off the face of the earth when they’d done nothing but run some errands; others killed leaving their offices, others leaving school. That voice said that for the last three days, since Wednesday, he’d had a feeling things were about to disintegrate. That voice told me what was said in the places he found himself, where he lurked unnoticed because he kept his mouth shut. What was said there was unbelievably violent, a kind of violence he’d forgotten, either because he was naive or he wanted to believe the past was past and we were headed for new times.

That voice, scratchy, strangled, emotional, said the man who was speaking didn’t know why he’d done the things he’d done in his life if it was only to discover he was still right where he’d started. Even if he’s a boss, even if he had a house built that proves he’s tried to better himself—a house that didn’t have a finished roof because he’d intended to build higher and higher—and not just for him but for his kids too. To forget the mud on his heels, the tiny hamlet even smaller than the one we were in; to forget, in that village, a street even narrower than the one we were on; to forget, finally, on that street, a house, a cabin, even smaller than the one we were in front of. A miniscule village, microscopic, incredibly dark, with all the cottages made of dark wood—not a single one painted white, not a single one that looked finished, unprotected wood that in the best case turned grayish under the rain and sun in that infinitely tiny village where he was born. That voice said there was absolutely nothing wonderful about his childhood, a childhood he had to endure, nothing that sang, nothing that spoke to the joy of going to the river for water and all that kind of bullshit you read about in books. No, just a real hard, brutal life—violence, mockery, and cruelty as survival strategies. Mockery was simply a way of devouring others, devouring yourself—chewing on your arms, legs, face, eating yourself so that nobody else could consume you. Faced with such cruelty, the only escape was through bleak comedic relief, dark humor: nothing bothered you because nothing mattered.

That voice said they made fun of his skinny legs, his crooked teeth, his black skin—absolutely black skin, which became a symbol of something very bad in a country where nobody talked about race, where racial hatred wasn’t supposed to exist because we’d all been freed; everybody was free, right? Everything depended on where you were in the hierarchy. That man I didn’t recognize said he used to laugh a lot, but that each time he laughed he was able to see in the eyes of those around him a profound sadness, as if they were saying, So that’s what you really think of me. And nowhere did anybody have a thought that would give you hope, push you a little further, help you believe in yourself; no concession to goodness. You had to be the most violent, to hit, punch, pound the table, throw stones, yell, act like a tough guy, test other people all the time.

And the voice continued:

“I’m going to tell you a story that keeps me awake at night, Guy-Albert. My friend Joseph, my sister Augustine, and I are all around an open fire and Joseph has a spoon in his hand. We watch it

get red hot and then, without warning, Joseph grabs the spoon and presses it into Augustine’s shoulder. He burns himself, of course, but it hurts less than it does Augustine, whose skin crackles as it burns—less than it hurts me, my gaze burning into him, as I sit there terrified. My sister doesn’t budge, as if she had no choice but to take it—not a scream, just a small sound quickly muffled, probably from surprise. She let it happen, no tears in her eyes, no anger, just a kind of furious desire to be stronger than the pain . . . What keeps me from sleeping, Guy-Albert, is trying to understand where Joseph got the idea, why Augustine was so sure she had to accept and submit to that torture.”

I suddenly saw those old drawings of slaves being marked by hot irons, those things that happened a long time ago but have stayed with us. All that came back to me, but I didn’t speak.

And then the voice added:

“You did the right thing. Nothing, not even a three-floor house, can justify massacring children, brothers, friends because people want a raise of a couple dollars.”

He stopped, waiting for what he’d just said to sink in. I was floored by what he’d admitted. We’d need some pretty solid machines, the best tools, to clean up the discussion shaping up in front of us. All the shovels, the pickaxes, the forklifts, the trowels, the sifters—sifters as big as the island itself—to separate out the muddy past. All those tools danced around me, around us, two men seated in a car while night was falling, two builders whose unfinished construction was already starting to crumble.

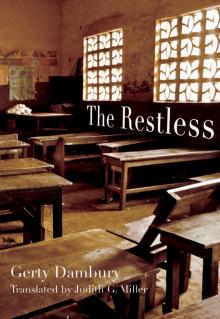

The Restless

The Restless